Déja Vu:

Lessons from the Spanish Flu Pandemic

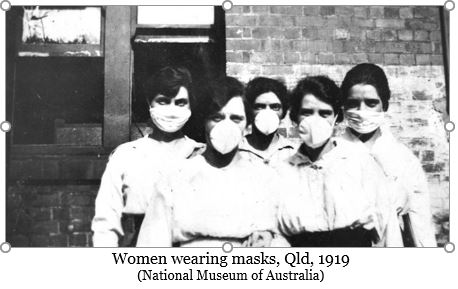

Wearing masks in a Sydney park, 1919 (National Museum of Australia)

Wearing masks in a Sydney park, 1919 (National Museum of Australia)

In 1919 my maternal great-grandmother, Mary O’Brien, died from the Spanish flu. She was in her late thirties and left three daughters behind – May, Anne and Kathleen. To all intents and purposes, the girls were orphans, as their father had decamped some years earlier and was presumed dead. (He wasn’t, and lived until 1948, but that’s another story.)

Being orphaned during a pandemic must have been a devastating experience and it certainly left its legacy on all three girls, albeit in different ways. At sixteen, my grandmother, May, was the eldest of the trio. The pandemic left her with a life-long obsession with hygiene. Among other things, I recall that she always made me scrub my hands after touching coins and banknotes. Canned food couldn’t be placed in the pantry before the cans were wiped down with disinfectant. Towels, bed linen, handkerchiefs and dishcloths weren’t just washed; they were boiled rigorously.

As a child I found these measures a bit odd, even extreme, but it's only been recently that I twigged to the reason for them. Obviously I’d heard of the Spanish flu and knew my great-grandmother had been a victim of it, but I didn't know of its horrific impact. And although we studied World War I at school, the 1919 pandemic which followed was virtually a footnote, if it was dealt with at all. Yet now it all makes sense, and here I am in 2021, behaving just like my grandmother – refusing to use cash, wiping down surfaces with disinfectant, quarantining packages, constantly washing my hands and, of course, wearing a mask whenever I'm out and about.

But there was more to the story of Mary O'Brien's death from the Spanish flu. You see, Mary liked to wear tight Edwardian-style corsets, even when she was at home, and even when she was suffering from a chest infection. That last morning, Mary asked her favourite daughter to lace up her corset. May had noticed her mother's cough and tied the corset loosely. 'Tighter!' her mother demanded. So May pulled the laces till they were taut. Suddenly her mother broke into a coughing fit and collapsed. There wasn't time to fetch a doctor, and Mary O'Brien died soon after. I often wonder whether her oldest daughter felt at least partly responsible for her mother's death. She certainly retold the story many times over the years as if, in the re-telling, she might assuage her guilt.

At the same time as May was dealing with life as an orphan with two little sisters, my paternal grandmother, Maude, was working as a nurse. I don’t ever recall her talking about that period. Like her husband, Ted, who served on the Western Front and was gassed at Messines, she may have decided the events she witnessed were too horrific to share with anyone.

My paternal grandmother aged 18 in 1919

In 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I began researching a possible novel set during the Spanish flu and inspired by the real events involving my orphaned grandmother. As I read old newspapers online and pored over medical papers produced at the time, I began to see similarities between the 'pneumonic fever' and Covid-19, and the more I read, the more depressed I became. After a month or two, I abandoned the research. The last thing you want to be doing during a national lockdown is to read about a pandemic that killed at least 50 million people! So I returned to a manuscript I had finished in late 2019, just before the bushfires, a novel called 'Camille Dupre', and released it free online in May 2020, with the request that readers consider making a donation to a Covid-related charity of their choice.

Although I abandoned my research, the notes I'd made remained on my laptop. Recently I re-read them and decided to write this article. As we all struggle to deal with the ongoing ramifications of COVID, it’s important to look at the pandemic of 1919 for insights into our current situation.

Admittedly, we’ve come a long way in terms of medicine and technology. Yet, in spite of all those 21st century innovations, the world has been overcome by a lethal virus in much the same way that it happened a hundred years ago. This time, however, its spread has been exacerbated by another innovation which was in its infancy in 1919 – air travel. Back then, the spread of the virus to Australia was considerably slower, taking place via trains and ships bringing soldiers back home. Nowadays, it only takes an unmasked limo driver and an international flight crew, and in a matter of days or weeks, a city with no cases can be in lockdown with over a hundred cases!

Human error and sheer stupidity will always play a part, even in a high-tech world.

Public Health Measures

Quarantine

Then

By the second half of the 19th century, there were quarantine stations at the entrance to many of Australia's key ports. They weren't foolproof but, in general, they worked well to protect the population from deadly imported epidemics such as cholera. Nowadays they are obsolete and have become historic curiosities.

Sydney's North Head Q-station held off the Spanish flu for several months. In the end, it arrived in Sydney via a returning soldier who took the train up from Melbourne.

Now

During the Covid pandemic of 2020/21, those entering the country have generally been quarantined in hotels designated for the purpose, but not purpose-built. This system has failed many times, and in June 2021, after 16 months of procrastinating, there is now a rush to build bespoke facilities similar to the existing Howard Springs in the NT. Why weren’t new facilities planned and built earlier? No-one in government can provide a satisfactory explanation.

Practical Measures

In February 1919, a suite of protective measures was announced by the NSW government via the newspapers. ‘Masks versus the Microbe’ was the headline in the Sydney Morning Herald of Feb 4, 1919. This was the list, exactly as it appeared.

- Hygiene

- Masks Masks Masks

- No mass gatherings

- Avoid overcrowding

In addition, race courses, picture theatres, dance halls, schools and churches were closed.

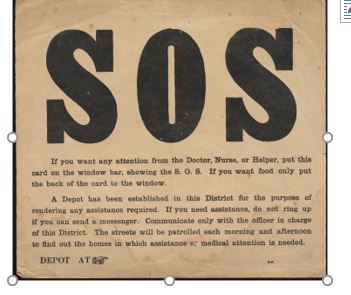

An SOS card from 1919.

It’s important to remember that very few people had telephones back then. So, people were given cards to place in their windows in the event that they required help. The side with the cross indicated you needed urgent medical attention (which often arrived by horse-drawn ambulance) and the reverse side signalled you needed food or other supplies.

Some Parallels

A Zoonotic Disease

Like Covid (SARS-CoV-2), the Spanish flu was a zoonotic viral infection. And just like Covid, the exact origins are murky. However, we do know that both diseases jumped from animals to humans. One theory about Spanish flu is that it may have come from rats which infected chickens or pigs on farms surrounding the battlefields of France.

An interesting footnote – back in 1919, it was generally assumed that the Spanish flu was bacterial. That’s because nobody really knew about the existence of viruses - they were too small to be seen through the microscopes of that time.

After Effects

Spanish flu was a tricky disease affecting people in many different ways. Like Post Covid Syndrome (commonly known as ‘long Covid’) there were sometimes lingering after-effects, among the worst being a condition which resembled (or actually was) Parkinson’s disease that developed decades later. There is even a theory that Hitler’s Parkinsonian symptoms may have been a result of him catching the Spanish flu in the trenches at the end of World War I.

Inflammation and over-reaction of the immune system occurred in many serious cases of the Spanish flu, as it has done with Covid. Today we call it a ‘cytokine storm’ and epidemiologists postulate that it is not just a factor in causing severe illness but also a cause of long-term issues.

Snake Oil Remedies

Just as we’ve seen crazy treatments for Covid espoused on the internet over the past 16 months, there were snake oil remedies and general quackery related to the treatment of the Spanish flu. And like the bizarre cures suggested by Donald Trump (to the horror of Dr Fauci), many of the 1919 remedies were toxic.

Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories are nothing new. In 1919 one of the weirdest was that the Germans were adding Spanish flu microbes to exported Bayer aspirin. During the current pandemic the internet has run wild with ridiculous theories that don't bear repeating here.

Contact tracing

Then . . .

If you’ve heard of ‘Typhoid Mary’, you’ll know that she was an asymptomatic case, discovered by traditional ‘detective’ work.

Her real name was Mary Mallon and she was an Irish-born cook, working at various locations in New York. When typhoid broke out in New York in 1907, a sanitary engineer by the name of George Sober began to suspect Mary because of her job as an itinerant cook and the fact there were outbreaks in the places she had worked. He followed her around the city, hoping to obtain a stool or urine sample to test! Not surprisingly, she didn’t oblige. So he decided to check her workplaces and soon realised she was a ‘silent’ carrier, spreading the disease wherever she went. Not only that, his investigation proved Mary was the initial cause of the outbreak – what we now call the ‘index case’ or ‘patient zero’.

Now. . .

Today, contact tracing still involves hands-on detective work such as phone calls and face-to face interviews but digital technology makes the logging and interpreting of that data so much faster and more reliable. And, of course, there are tools such as QR codes, that provide a list of the places an infected person has visited and when. But, it’s not foolproof. Ultimately it depends on people remembering to log in at venues.

Vaccines

By 1919, there were vaccines for small pox and a few other deadly diseases such as cholera and rabies but it wasn't until the 1920s that vaccines for diphtheria, scarlet fever and whooping cough were developed. A vaccine was never an option to deal with the Spanish flu.

What gives us all hope in 2021 is that there are now several effective Covid vaccines, and the possibility of 'herd immunity' is no longer a pipe dream. And, if there's a bright light in this pandemic, it's the work of the scientists who developed these vaccines in record time. On the dark side, Australia has endured major issues related to procurement and distribution, both of which are Federal Government responsibilities. We've been told by the Prime Minister: 'It's not a race, it's not a competition.' If this isn't the race of our lives, I don't know what is!

The Future

The sad fact is that zoonotic diseases will continue to rampage across the planet as long as we plunder our natural environment and the animals that live there. The list of existing zoonotic diseases is scary – Ebola, Zika, SARS and MERS (both coronaviruses), Swine flu, Ross River fever, Lyme disease and many, many others. Worse still, epidemiologists warn us that there are more to come if we continue our pattern of destruction and abuse of the world around us.

Deborah O’Brien - Writer

29 June, 2021

Bibliography and Further Reading

https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/masks-are-not-a-panacea-but-are-the-step-we-needed-to-take-20200720-p55dqh.html

https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/stories/pneumonic-influenza-1919

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2020/jun/economic-effects-of-the-spanish-flu.html

http://www.gp.org.au/SpanishFlu.php

https://www.publish.csiro.au/ma/pdf/MA20048

https://tvblackbox.com.au/page/2020/05/28/lest-we-forget-this-week-on-australian-story/

Matt Bamford, ABC Radio, ‘Coronavirus response may draw from Spanish flu pandemic of 100 years ago’

The ‘Camille Dupré’ Songbook

Charles Trenet, French composer and singer

Whenever I’m writing historical fiction, I try to play the popular music of the period in the background because it evokes the mood of the era better than anything else.

For ‘Mr Chen’s Emporium’, the soundtrack included Strauss waltzes and the work of Stephen Foster (1826 – 1864), including his poignant ‘Beautiful Dreamer’, which became Charles Chen’s theme song.

When I was writing ‘The Rarest Thing’, which is set in 1966, the playlist was the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Simon and Garfunkel, the Hollys and the Easybeats, among others. In almost every chapter, there seems to be a Sixties song that defines the heroine Katharine’s state of mind at that particular moment.

‘Camille Dupré’ is set in the 1930s and ’40s, which just happens to be one of my favourite periods in popular music. In 1930s’ France, the vibrant cabaret scene produced many stars including a young Edith Piaf, Tino Rossi, Maurice Chevalier, Jean Sablon, ‘Mireille’ and the amazing Charles Trenet.

But even though the French loved their home-grown stars, they also listened to American songs on the radio, just as they went to see American movies at the cinema. That is, until the Nazis banned American music, particularly ‘Swing’ and jazz, which they considered the most subversive genres. During the Occupation, Camille was one of many who continued to listen to banned radio stations such as Radio Londres.

Here are some of the songs that form the soundtrack to Camille Dupré's story.

‘Boum!’

In 1930s France, one of the most talented musical stars was Jean Trenet whose double-breasted suit, smart fedora hat and jaunty manner were his trademark. His biggest hit was ‘Boum!’ (1938), a sweet, playful song that compares falling in love to the heart going boom. Although 'Boum!' is filled with joie de vivre, the irony is that Trenet wrote it at a time when the world was heading towards war.

With different lyrics, the song went on to be used by both the occupying Nazis and the Resistance as a rallying song. Trenet, a leftwinger who hated the puppet Vichy regime, refused to socialise with the German officers who attended his concerts.

If you've seen the film 'Amélie' starring the delightful Audrey Tautou, you'll recall 'Boum!' providing the soundtrack to the scenes where the heroine falls in love. The song has also been used in World War II documentaries about Occupied France.

You can see Jean Trenet performing the song on YouTube.

‘Long Ago and Far Away’

This song was composed by Jerome Kern with lyrics by Ira Gershwin – you couldn’t find a more talented duo.

At one point in the novel (I can’t be more specific without giving away too much), Camille finds herself listening to this beautiful and poignant American song. In many ways, it sums up her situation.

You can listen to the original 1944 version by Jo Stafford on YouTube. Since then, the song has been recorded by just about everyone, from Frank Sinatra and Mel Tormé to Rod Stewart (who actually does a very good version of it).

‘I’ll Be Seeing You’

Composed in 1938 by Sammy Fain with lyrics by Irving Kahal, this song resonates with yearning for a lost past. It wasn’t until 1944 that it became a hit when it was featured in the film of the same name starring Ginger Rogers and Joseph Cotton.

‘They Can’t Take That Away from Me’

Created in 1937 by those immensely talented brothers, George and Ira Gershwin, ‘They Can’t Take That Away from Me’ was sung by Fred Astaire to a tremulous Ginger Rogers in the 1937 film ‘Shall We Dance’. Although Astaire’s dancing was far superior to his singing, his version of this song is absolutely captivating.

Deborah O’Brien

22 May, 2020

Proverb Bookmarks

A GIFT FOR YOU

DOWNLOAD YOUR FREE BOOKMARKS

USING THE LINK AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

As a reader, you can never ever have enough bookmarks, especially if you’re the kind of person who has several books on the go at the one time.

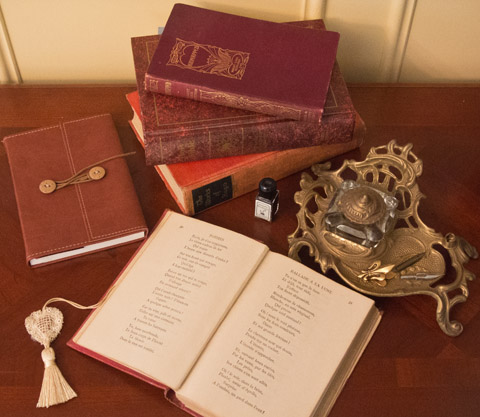

So I’ve designed a range of bookmarks for you to download and print, featuring proverbs about hope and happiness from my e-novel, 'Camille Dupré'. Yes, I know it's a digital book, but print books still predominate and I, for one, am glad of that. I love a glossy embossed cover and the smell of printer's ink, but sometimes that's not a viable option.

At the end of last year I finally finished a manuscript I'd been working on for years, set during the Nazi Occupation of France. But before I knew it, the coronavirus had struck and it dawned on me that we were facing our own deadly battle, but against an invisible enemy. That was when I decided to release the book free with the request that readers might consider making a donation to a COVID-19 related charity. There was no question of producing a print book. It had to be an e-book, something that could be formatted quickly and easily accessed during lockdown.

Although most e-books look rather plain, I was able to incorporate some decorative touches you won't find inside typical digital books (such as coloured text), but technical constraints forced me to remove some of the more exuberant features that had appeared in my original file but wouldn't convert smoothly to the PDF format.

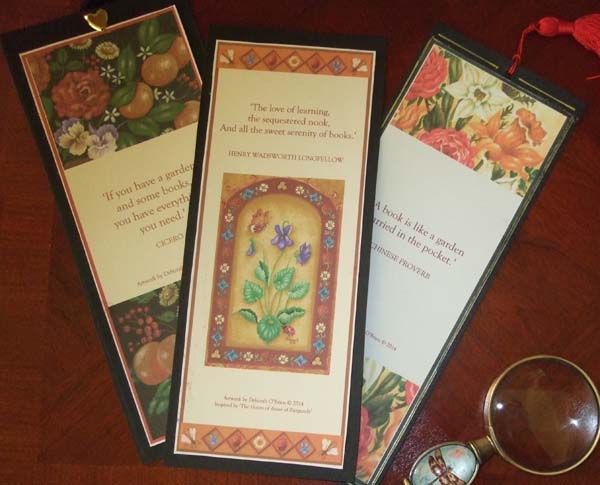

Bookmarks are another story. There are no creative constraints when it comes to making and decorating them. Below are a few ideas for embellishing your bookmarks. But, if you'd prefer, you can simply print them onto photocopy paper and cut them out - they will be flimsy but will serve the purpose.

If you have some paper that's a little heavier than normal photocopy paper but can still safely run through your printer, you could try that. Otherwise, if you want to make a sturdier bookmark, you can print on ordinary 80gsm photocopy paper, cut out your bookmarks and glue them to coloured cardboard. These personal touches make for a very smart bookmark, particularly if you add a mini-tassel or a decorative split-pin like the heart-shaped one in the photo.

Ideas for finishing and decorating bookmarks.

I designed these for the release of 'A Place of Her Own' in 2014.

Keep the bookmarks for yourself or give them to family and friends. They're also perfect for sharing with your book club.

Download your 'Camille Dupré' proverb bookmarks here.

Deborah O'Brien

27 May 2020

Researching ‘Camille Dupré’

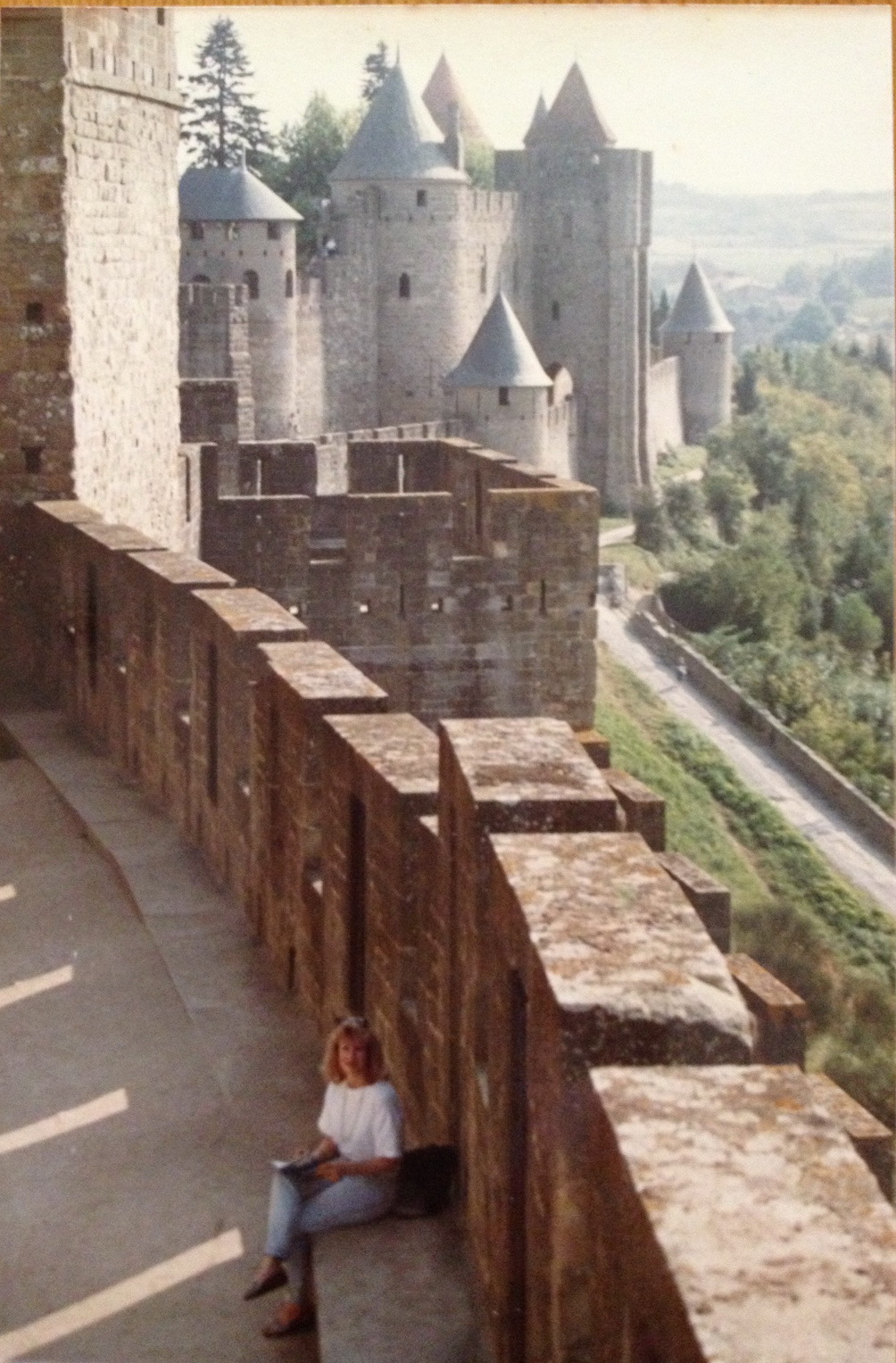

Author at Carcassonne, 1992

Writing historical fiction can be a balancing act between creating an interesting story and indulging the writer’s fascination with the facts they’ve discovered during their research. An author can easily overload a book with chunks of historical detail that are likely to slow the pace of the story and bore the reader. In literary jargon, this is called ‘information dumping’.

I remember sending the draft of my first historical novel to an assessor for an appraisal. When the manuscript came back in the post, whole sections had been crossed out with a highlighting pen. Yes, you guessed it – those sections contained unnecessary historical material which was disrupting the flow of the narrative. To this day, that particular book remains in the proverbial bottom drawer, but I did learn an important lesson.

Ever since then, I've tried to picture the historical framework of the book as the infrastructure of a house. Like the wiring and plumbing, the historical component needs to be in the background quietly doing its job, but we don’t need to see the wires and pipes.

In a field of sunflowers, Languedoc 1992

If you’ve read the ‘Author’s Note’ at the end of ‘Camille Dupré’, you’ll know I started this project a very long time ago and it has been informed by my background in French and German language and history, as well as my travels in Europe.

I’ve always loved southern France, especially the area around Montpellier, and it seemed the obvious place to set the story. I have to confess I didn’t do a lot of geographical research because I was already familiar with the location. In fact, I had walked almost every street in the city centre, getting lost on occasion in the labyrinth of mediaeval alleyways at its heart but eventually finding my way out, often emerging into the vast, sunlit square known as the Place de la Comédie.

Montpellier is an ancient city with wide Paris-style boulevards and narrow laneways. That makes it particularly intriguing. It’s also home to one of the oldest and most respected universities in the world, whose courses have attracted international students for hundreds of years. All those elements were perfect for the storyline I had in mind.

Rue Foch, Montpellier - echoes of Paris

(Photo: D.O'Brien)

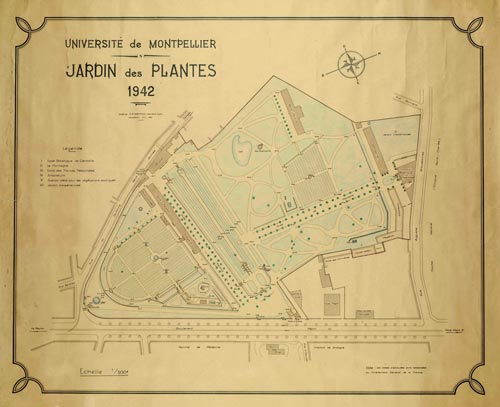

I was fortunate to find a map of Montpellier circa 1945 (below), which became my guide as I worked on the story. You can see the Place de la Comédie towards the righthand bottom corner. The Hôtel de Ville (town hall) precinct where I located the lending library is almost at the centre just south of the Cathedral de St Pierre. The Jardin des Plantes is in the top left corner.

The Prison is situated north of the Arc de Triomphe (map reference 8X) next to the Palais de Justice. At the centre of the western edge of the map is the magnificent Promenade du Peyrou and the Château d'Eau.

On the Rue Foch, just opposite the Préfecture is the Place des Martyrs de la Résistance, created after the Liberation of France to memorialise those who died resisting the Nazi regime in the Montpellier area (map reference 8Y). This square is now considered the centre of the city.

Michelin Map of Montpellier circa 1945.

Jardin des Plantes (Botanic Gardens), Montpellier, 1942.

The Sunken Garden is in the centre overlooked by the artificial 'mountain'.

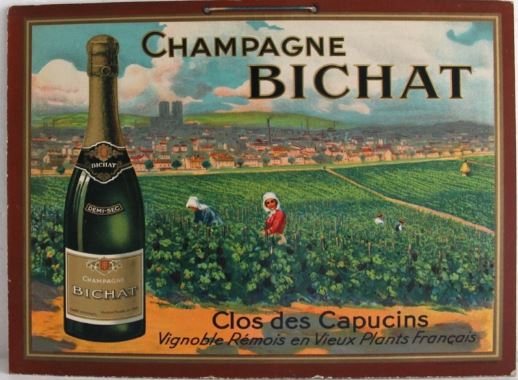

Not far from the city itself there are picturesque vineyards and olive groves, which provided the perfect place for Camille to live. (After all, the literal meaning of her name is 'Camille of the Fields'.) I had to paint a picture of life at the Domaine St-Jean-de-la-Rivière without going into too much technical detail about winemaking. Old black and white photos from 1930s' France, depicting rustic scenes such as a horse pulling a harrow or grape pickers filling wicker 'comportes', inspired the passages where the family are tending the vines and harvesting the grapes.

Vintage poster for Bichat Champagne.

This is mentioned in Chapter 34.

As an artist who writes (or vice versa), I’ve always been inspired by all things visual. When researching a particular era, I seek out the realia and ephemera of everyday life – objects, posters, signs, advertisements, maps, photos, clothing catalogues, recipes and, of course, newspapers. Thanks to the internet, we're able to view many of these items online.

Newspapers from the early 1930s were particularly important in informing the scenes where Camille's father shares a bottle of Merlot with Kurt and they discuss the news of the day at a time when political unrest and economic instability are increasing at a frightening pace and the spectre of Hitler's growing power is already casting a shadow over Europe.

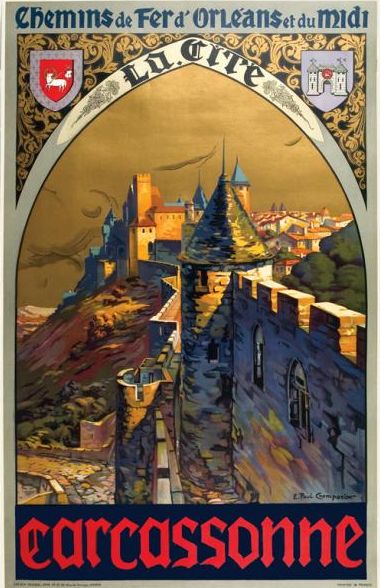

Classic railway poster designed by E. Paul Champseix in 1925.

This is the poster that Kurt sees on the train to Montpellier

and which inspires the day trip to Carcassonne at the end of summer in 1931.

Film poster: 'Le Comte de Monte Christo'.

Camille and Kurt go to see this film at the Gaumont cinema in Montpellier

in June, 1943, just after its release.

The 1943 French production was made under Nazi supervision

but still managed to convey a message about overcoming tyranny.

I’m a movie buff, which means films seem to play a big part in my stories. Initially, I didn’t know much about French cinema in the 1930s and early ’40s, but I soon found myself watching a variety of old French films on YouTube. Not only do films with contemporary themes capture the spirit of the period, they also give you a feel for how people dressed and spoke, the vehicles they drove, the houses they lived in.

Citroen AC4 Berline 1927.

This is the car (but in black) that Kurt hires for the day trip to Carcassonne.

You will find details of my other reference materials in the Author’s Note at the end of the novel.

Finally, I must offer a disclaimer. Even though I like the factual details and timelines to be correct, I don’t purport to be a purist. Sometimes there has to be a compromise for the sake of the story. After all, this is an imaginary tale in an historical setting, not a work of historical non-fiction.

You can download the free e-novel here.

Deborah O’Brien

15 May, 2020

My Top Three Tips for Aspiring Authors

Pic: DOB

Let me preface this article by saying that I’m always reluctant to give advice because every writer has his or her own approach. Nevertheless, here are some general tips to get you started on your writing journey:

1. Write from the heart.

Don’t be afraid to work from your emotions – you can always edit later, if necessary. Here's what Wordsworth had to say on the subject:

‘Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart.’

2. If you really want to be a writer, don’t put it off.

Even though your life might be too busy to contemplate penning a 100,000-word novel, there are other possibilities such as blogs, short stories or even a novella. George Eliot (aka Mary Ann Evans), who was arguably the greatest Victorian novelist, once said:

‘It’s never too late to be what you might have been.’

And equally, it’s never too early to start!

3. Revise, tweak and polish your manuscript until it shines.

You can never do enough revisions. Don’t consider sending off a manuscript to an agent or a publisher until you know it's the very best version you can produce. A big mistake that first-timers make is to send their manuscript too early – I know because I did it!

Always ensure the ‘infrastructure’ is correct – the grammar, syntax and spelling. Proofread the text thoroughly for mistakes (and don’t just rely on the Spelling and Grammar Tool on your computer).

Reading the manuscript aloud is always helpful in the checking process, not just for spotting typos, but also for checking the flow of the text and identifying clunky language.

I always read the final proof of every novel aloud – it takes about a day but it’s worth the effort because I’ve found mistakes that all of us, the structural editor, line editor, proof-reader and yours truly, have missed in just silently reading the pages.

Deborah O’Brien

20 March, 2020

Adapted and expanded from part of an interview I did with the wonderful Jodi Gibson.

Subcategories

Home in the Highlands

Home in the Highlands blogs