I’ve always associated the colour black with mourning. Black arm-bands, high-necked black dresses, black veils, jet jewellery. Recently I've been researching mourning practices during the Victorian era for my book, The Jade Widow. What I've learned is that there was a convention known as ‘half-mourning’, which allowed the grieving widow to wear lilac after the first year or two had passed.

For those who have suffered the loss of a loved one, you will know there is no such thing as grieving by halves. Not in an emotional sense. Nor can anyone set a timeline on the grieving process and expect a person who has been bereaved to follow it. ‘Grief has its own timetable,’ as one of the characters in my book says. ‘You can’t expect it to depart at a set time like a steam-engine.’

All the same, I'm drawn to the idea of lilac as a transition from sombre black and greytones to lighter, brighter hues, reflecting the journey from darkest grief towards hope and renewal.

But why lilac rather than any other colour? Well, it seems that lilac bushes have been a symbol of love and loss since ancient times. Whether this special significance derives from the flowers themselves or the lingering fragrance or even the heart-shaped leaves, I don't know.

As for the sudden popularity of the colour lilac in the mid-1800s, there’s a very practical reason. Until that time, the colour had been extracted from mallow plants or from the glands of mollusks. Both processes would have been labour-intensive and expensive. No wonder purple was the colour reserved for royalty! Can you imagine how many mollusks would have been sacrificed to make a single vial of lilac dye? I don’t even want to think about it!

In the spring of 1856 everything changed when eighteen-year-old London student,  William Perkin undertook a chemistry experiment which produced a lilac-coloured residue. Realising its potential as a synthetic dye, he dubbed it ‘mauveine’ and applied for a patent. In 1862, the year after Prince Albert died, Queen Victoria was seen wearing lilac – or mauve, as it came to be known - to the Royal Exhibition. And suddenly it became the hue du jour.

William Perkin undertook a chemistry experiment which produced a lilac-coloured residue. Realising its potential as a synthetic dye, he dubbed it ‘mauveine’ and applied for a patent. In 1862, the year after Prince Albert died, Queen Victoria was seen wearing lilac – or mauve, as it came to be known - to the Royal Exhibition. And suddenly it became the hue du jour.

The colour lilac plays a symbolic role in my novel-in-progress, 'The Jade Widow' (September 2013), which is set in 1880s' Australia. But I had better not go into the details for fear of giving too much away. Suffice it to say that the widow in question is so reluctant to replace her black clothes with something less sombre that her friends have dubbed her ‘the black widow’.

Will she remain the grieving widow forever or will she embrace life again? I'm afraid you’ll have to wait and see!

Special thanks to my friend Jan N. who first alerted me to the significance of the colour lilac in Victorian times.

Photo taken by my husband this summer before the heatwave - it's a buddleia not a lilac.

Deborah O’Brien

January, 2013

Christmas is a very special time at our house. This morning my husband took some pictures of our Christmas tree decorated with the ornaments friends and family have given me over the years. Each one tells a story and reminds me of the giver. Some of them are handmade - exquisite little pieces of cross-stitch, folk art, beadwork and every kind of art and craft. But my favourite remains the clothes-peg reindeer my son made in kindergarten.

Over the years a dear friend of mine, who lives in the country, has given me the most beautiful painted Santas, as well as quilted and embroidered wall hangings. Isn't the Santa gourd wonderful?

My garden looks like Christmas too - the gardenias and hydrangeas are in bloom. Everyone asks me how I manage to grow such large gardenia flowers - I really don't know. I have an entire hedge of them, but only one bush produces big blooms. Maybe I'm just lucky.

Wishing you a joyful Christmas and a happy and healthy New Year!

Deborah

Deborah O'Brien

December 1, 2012

If you've read 'Mr Chen's Emporium', you'll know that it contains a storyline about alpacas, which appears in the modern-day thread of the book (alpacas were only introduced to Australia in 1988*). One of the characters in the novel is always confusing them with llamas. I'm not exactly sure of the biological difference between alpacas and llamas myself , except that llamas are bigger, but I've always thought alpacas are cuter.

However, I'm now wondering if I might have been wrong about that. You see, my husband recently showed me these pictures he took many years ago whilst mountaineering in the Andes. He and a group of friends from his university in Canada flew down to Peru with the intention of climbing a particular mountain which had never been climbed before. Unfortunately the leader left the map behind! So they decided to catch a bus from Cuzco and after a very long trip they were dropped off in a valley at the start of an old Inca trail. They climbed it for several hours, reaching about 15,000 feet. That was where these pictures were taken.

Did they ever climb the previously unclimbed mountain? They weren't really sure. They did climb to about 18,ooo feet, where they looked towards a distant range of mountains. "I think that's where we should been climbing," said the leader.

Aren't the llamas gorgeous? Here's an alpaca picture (crias) so that you can compare the two.

* According to a fact sheet from the SA Department of Primary Industry and Resources, alpacas were first introduced to Australia in 1858 but the initiative failed. I imagine that the alpacas must have died, perhaps from the heat. Very, very sad.

Since writing this article, I've discovered several contemporary articles in 'The Argus' (courtesy of the Trove website run by the National Library of Australia), referring to the arrival of the alpacas.

Deborah O'Brien

December, 2012.

Only one of the following productions is specifically referred to in the text of MR CHEN’S EMPORIUM, but as a movie and television buff myself, I like to imagine that these are some of Angie Wallace’s favourite Westerns.

Gunsmoke

This was everyone’s favourite Western TV series in the Sixties, along with Bonanza, Rawhide (in which a young Clint Eastwood rose to fame) and Wagon Train. As a kid, I always wanted to be Miss Kitty (Amanda Blake). She was the prettiest woman on television. Thinking about it now, the fact she ran a saloon should have given me an indication that Miss Kitty was possibly not a Western lady in the school marm tradition. Then again, her relationship with the Sheriff always seemed to be oddly circumspect.

The Magnificent Seven

Based on Kurosawa’s classic The Seven Samurai, this is the quintessential American Western movie of the early Sixties. Brimming with sex symbols including Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen and a young Robert Vaughan (still to become the ‘Man from UNCLE’ and better known nowadays as the elderly Albert Stroller from the late lamented Hustle), it is the archetypal story of a band of heroes saving an oppressed populace from an evil villain.

The Outlaw Josey Wales

When Angie Wallace makes an allusion to an attractive and enigmatic outlaw, it’s Clint Eastwood’s Josey Wales I have in mind. In this 1976 film Eastwood becomes an outlaw after the massacre of his wife and children. The film was directed by Eastwood, the second in a series of Westerns he made from the Seventies, culminating in 1992’s superb Unforgiven for which he won an Academy Award for Direction.

The Quick and the Dead

Although this film is rather patchy overall, Sharon Stone is convincing as its gunslinger heroine. And you won’t find a better Western villain than Gene Hackman’s Herod. Imbuing his character with charm and evil in equal measure, Hackman looks great in a long black coat and Stetson hat. What’s more, he does a menacing smile better than anybody else.

Deborah O’Brien

November, 2012

![]() Recreational Sewing in Cesarine

Recreational Sewing in Cesarine

Recently, while I was browsing through some boxes of memorabilia, I came across my old primary school report cards. They date back to an era when the subjects (now known as learning areas) were: Reading, Composition, Spelling, Writing, Arithmetic, English (i.e. grammar), Social Studies and something with the odd name of ‘Recreational Sewing’.

Suddenly all the memories flooded back. Sewing had been the curse of my primary school days, followed very closely by arithmetic. I had tried a couple of ploys to get out of needlework. The first was to offer to spend the sewing lesson doing extra maths. To my childish way of thinking, that seemed like a very reasonable exchange. The school, however, didn’t agree. According to my class teacher, the curriculum required that I undertake two hours of ‘handcrafts’ a week and there was no room for negotiation.

So I convinced my mum to write a note asking if I could do basket-weaving instead of needlework. (You see, in that long-ago pre-feminist era, girls did sewing lessons and boys made waste-paper baskets.) But that ploy failed too when the headmaster sternly reminded me that girls needed to learn how to sew. ‘It’s a foundation for your future life as a housewife,’ he said. After his pronouncement, there was no further court of appeal. Ahead of me lay four years of compulsory sewing. Four years of torture involving needle and thread.

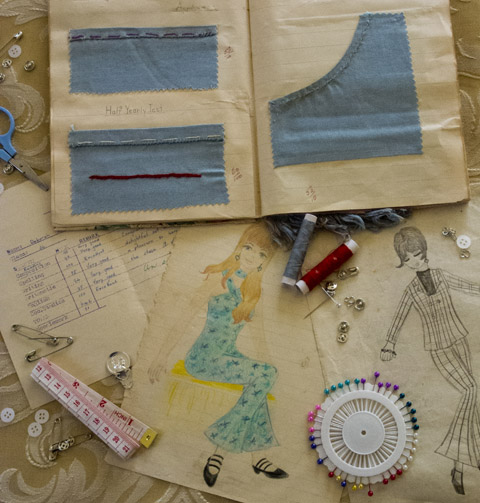

Back in the present day, I continued to trawl through the boxes of memorabilia, only to find the document which held the record of my inglorious needlework career from ages seven to eleven – my sewing exercise book. It was still intact and neatly covered in wrapping paper decorated with flower fairies.

So what did I find inside? Well, the book begins promisingly enough with a pretty title page. (Title pages and lettering were my specialty.) ‘Excellent work’, the sewing teacher had written at the bottom of the page, accompanied by a penguin stamp. It was the last ‘excellent’ I was ever to receive in needlework lessons.

The next few pages are set out in columns headed ‘Article’, ‘Material’, ‘Start’, ‘Finish’ and ‘Marks’. In the ‘material’ column, the word ‘cesarine’ appears again and again. Cesarine? It sounds very Sixties and synthetic, doesn’t it? I Googled the word and discovered it was the ‘wonder cloth’ of the post-war years developed by a Sydney company called Caesar Fabrics. And it wasn’t synthetic at all but a kind of thick cotton which didn’t wrinkle and was popular for uniforms.

Using the aforementioned cesarine, I had made (in chronological order): a pin wheel, a needle case and a bag for my cotton thread. The bag must have been a mammoth task because I'd started it in September and didn’t complete it until December. The finished product received a mark of 5 ½ out of ten! Oh dear! No trace of it remains, nor of the other items.

In the subsequent years it appears that I made the following: a desk cover (whatever that was) an apron, a petticoat and panties, a huckaback guest towel, a throw over, a tray cloth and the piece-de-resistance of Grade 6, a ‘frock’. At the end of the year there was a fashion parade in which we modelled our ensembles in front of our parents. I don’t think I ever wore that ‘frock’ again – I hated it so much!

Now back to the sewing book. Each of the subsequent pages features samples of different stitches and techniques sewn on rectangles of the ubiquitous cesarine, the edges trimmed with pinking shears. The samples are covered in rusty marks which are most certainly ancient blood stains - the result of accidents with a needle or even a stray pin. How peculiar that my DNA is forever embedded in that cesarine.

Here are some of the tasks we were required to master: running stitch, top sewing, tacking a hem, chain stitch, rosebuds (rusty smudges everywhere), a French hem, sewing on of tape, a run and fell seam, shell hemming, blanket stitch , herring bone variations, backstitching, a continuous placket, buttonhole stitch, bias binding and darning a thin place (yes, that was the exact heading).

I seemed to be the only girl in the class whose cotton thread formed itself into a Gordian knot at least once every lesson, requiring me to go up to the sewing teacher’s desk and beg her to untangle it. ‘Deborah, how could you possibly get your thread in such a mess?’ she would ask in an exasperated tone. Which brings me to the teacher herself. One of the scariest people I’ve ever met. She never smiled. Well, at least, not at me. I can see her dour face even now.

Did I ever overcome my dislike of sewing and transform myself into an embroiderer or a quilter? I’m ashamed to confess that I didn’t. Instead, I did deals with my talented friends. I would paint a portrait of their child and in return they would make me a quilt, cross-stitch a sampler or embroider a cushion. My house is filled with exquisite needlework – none of it made by me!

And there’s an ironic twist to this story. As a teenager, I dreamed of becoming a fashion designer. You can see some of my youthful efforts on this page. I could draw the outfits on paper, but there was no way that I could ever make them. Sewing was anathema to me. That’s why my fashion design career ended before it began !

Deborah O’Brien

October, 2012

Subcategories

Home in the Highlands

Home in the Highlands blogs