Déja Vu:

Lessons from the Spanish Flu Pandemic

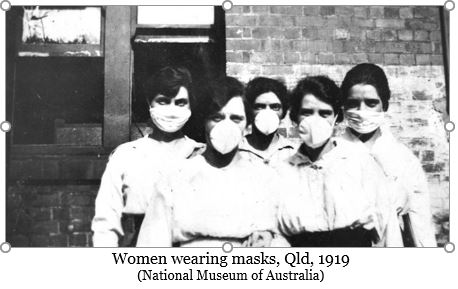

Wearing masks in a Sydney park, 1919 (National Museum of Australia)

Wearing masks in a Sydney park, 1919 (National Museum of Australia)

In 1919 my maternal great-grandmother, Mary O’Brien, died from the Spanish flu. She was in her late thirties and left three daughters behind – May, Anne and Kathleen. To all intents and purposes, the girls were orphans, as their father had decamped some years earlier and was presumed dead. (He wasn’t, and lived until 1948, but that’s another story.)

Being orphaned during a pandemic must have been a devastating experience and it certainly left its legacy on all three girls, albeit in different ways. At sixteen, my grandmother, May, was the eldest of the trio. The pandemic left her with a life-long obsession with hygiene. Among other things, I recall that she always made me scrub my hands after touching coins and banknotes. Canned food couldn’t be placed in the pantry before the cans were wiped down with disinfectant. Towels, bed linen, handkerchiefs and dishcloths weren’t just washed; they were boiled rigorously.

As a child I found these measures a bit odd, even extreme, but it's only been recently that I twigged to the reason for them. Obviously I’d heard of the Spanish flu and knew my great-grandmother had been a victim of it, but I didn't know of its horrific impact. And although we studied World War I at school, the 1919 pandemic which followed was virtually a footnote, if it was dealt with at all. Yet now it all makes sense, and here I am in 2021, behaving just like my grandmother – refusing to use cash, wiping down surfaces with disinfectant, quarantining packages, constantly washing my hands and, of course, wearing a mask whenever I'm out and about.

But there was more to the story of Mary O'Brien's death from the Spanish flu. You see, Mary liked to wear tight Edwardian-style corsets, even when she was at home, and even when she was suffering from a chest infection. That last morning, Mary asked her favourite daughter to lace up her corset. May had noticed her mother's cough and tied the corset loosely. 'Tighter!' her mother demanded. So May pulled the laces till they were taut. Suddenly her mother broke into a coughing fit and collapsed. There wasn't time to fetch a doctor, and Mary O'Brien died soon after. I often wonder whether her oldest daughter felt at least partly responsible for her mother's death. She certainly retold the story many times over the years as if, in the re-telling, she might assuage her guilt.

At the same time as May was dealing with life as an orphan with two little sisters, my paternal grandmother, Maude, was working as a nurse. I don’t ever recall her talking about that period. Like her husband, Ted, who served on the Western Front and was gassed at Messines, she may have decided the events she witnessed were too horrific to share with anyone.

My paternal grandmother aged 18 in 1919

In 2020 at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I began researching a possible novel set during the Spanish flu and inspired by the real events involving my orphaned grandmother. As I read old newspapers online and pored over medical papers produced at the time, I began to see similarities between the 'pneumonic fever' and Covid-19, and the more I read, the more depressed I became. After a month or two, I abandoned the research. The last thing you want to be doing during a national lockdown is to read about a pandemic that killed at least 50 million people! So I returned to a manuscript I had finished in late 2019, just before the bushfires, a novel called 'Camille Dupre', and released it free online in May 2020, with the request that readers consider making a donation to a Covid-related charity of their choice.

Although I abandoned my research, the notes I'd made remained on my laptop. Recently I re-read them and decided to write this article. As we all struggle to deal with the ongoing ramifications of COVID, it’s important to look at the pandemic of 1919 for insights into our current situation.

Admittedly, we’ve come a long way in terms of medicine and technology. Yet, in spite of all those 21st century innovations, the world has been overcome by a lethal virus in much the same way that it happened a hundred years ago. This time, however, its spread has been exacerbated by another innovation which was in its infancy in 1919 – air travel. Back then, the spread of the virus to Australia was considerably slower, taking place via trains and ships bringing soldiers back home. Nowadays, it only takes an unmasked limo driver and an international flight crew, and in a matter of days or weeks, a city with no cases can be in lockdown with over a hundred cases!

Human error and sheer stupidity will always play a part, even in a high-tech world.

Public Health Measures

Quarantine

Then

By the second half of the 19th century, there were quarantine stations at the entrance to many of Australia's key ports. They weren't foolproof but, in general, they worked well to protect the population from deadly imported epidemics such as cholera. Nowadays they are obsolete and have become historic curiosities.

Sydney's North Head Q-station held off the Spanish flu for several months. In the end, it arrived in Sydney via a returning soldier who took the train up from Melbourne.

Now

During the Covid pandemic of 2020/21, those entering the country have generally been quarantined in hotels designated for the purpose, but not purpose-built. This system has failed many times, and in June 2021, after 16 months of procrastinating, there is now a rush to build bespoke facilities similar to the existing Howard Springs in the NT. Why weren’t new facilities planned and built earlier? No-one in government can provide a satisfactory explanation.

Practical Measures

In February 1919, a suite of protective measures was announced by the NSW government via the newspapers. ‘Masks versus the Microbe’ was the headline in the Sydney Morning Herald of Feb 4, 1919. This was the list, exactly as it appeared.

- Hygiene

- Masks Masks Masks

- No mass gatherings

- Avoid overcrowding

In addition, race courses, picture theatres, dance halls, schools and churches were closed.

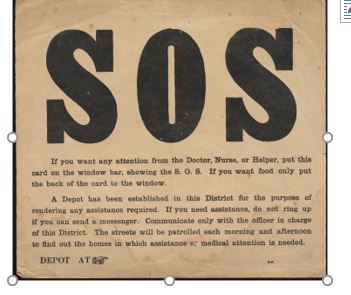

An SOS card from 1919.

It’s important to remember that very few people had telephones back then. So, people were given cards to place in their windows in the event that they required help. The side with the cross indicated you needed urgent medical attention (which often arrived by horse-drawn ambulance) and the reverse side signalled you needed food or other supplies.

Some Parallels

A Zoonotic Disease

Like Covid (SARS-CoV-2), the Spanish flu was a zoonotic viral infection. And just like Covid, the exact origins are murky. However, we do know that both diseases jumped from animals to humans. One theory about Spanish flu is that it may have come from rats which infected chickens or pigs on farms surrounding the battlefields of France.

An interesting footnote – back in 1919, it was generally assumed that the Spanish flu was bacterial. That’s because nobody really knew about the existence of viruses - they were too small to be seen through the microscopes of that time.

After Effects

Spanish flu was a tricky disease affecting people in many different ways. Like Post Covid Syndrome (commonly known as ‘long Covid’) there were sometimes lingering after-effects, among the worst being a condition which resembled (or actually was) Parkinson’s disease that developed decades later. There is even a theory that Hitler’s Parkinsonian symptoms may have been a result of him catching the Spanish flu in the trenches at the end of World War I.

Inflammation and over-reaction of the immune system occurred in many serious cases of the Spanish flu, as it has done with Covid. Today we call it a ‘cytokine storm’ and epidemiologists postulate that it is not just a factor in causing severe illness but also a cause of long-term issues.

Snake Oil Remedies

Just as we’ve seen crazy treatments for Covid espoused on the internet over the past 16 months, there were snake oil remedies and general quackery related to the treatment of the Spanish flu. And like the bizarre cures suggested by Donald Trump (to the horror of Dr Fauci), many of the 1919 remedies were toxic.

Conspiracy Theories

Conspiracy theories are nothing new. In 1919 one of the weirdest was that the Germans were adding Spanish flu microbes to exported Bayer aspirin. During the current pandemic the internet has run wild with ridiculous theories that don't bear repeating here.

Contact tracing

Then . . .

If you’ve heard of ‘Typhoid Mary’, you’ll know that she was an asymptomatic case, discovered by traditional ‘detective’ work.

Her real name was Mary Mallon and she was an Irish-born cook, working at various locations in New York. When typhoid broke out in New York in 1907, a sanitary engineer by the name of George Sober began to suspect Mary because of her job as an itinerant cook and the fact there were outbreaks in the places she had worked. He followed her around the city, hoping to obtain a stool or urine sample to test! Not surprisingly, she didn’t oblige. So he decided to check her workplaces and soon realised she was a ‘silent’ carrier, spreading the disease wherever she went. Not only that, his investigation proved Mary was the initial cause of the outbreak – what we now call the ‘index case’ or ‘patient zero’.

Now. . .

Today, contact tracing still involves hands-on detective work such as phone calls and face-to face interviews but digital technology makes the logging and interpreting of that data so much faster and more reliable. And, of course, there are tools such as QR codes, that provide a list of the places an infected person has visited and when. But, it’s not foolproof. Ultimately it depends on people remembering to log in at venues.

Vaccines

By 1919, there were vaccines for small pox and a few other deadly diseases such as cholera and rabies but it wasn't until the 1920s that vaccines for diphtheria, scarlet fever and whooping cough were developed. A vaccine was never an option to deal with the Spanish flu.

What gives us all hope in 2021 is that there are now several effective Covid vaccines, and the possibility of 'herd immunity' is no longer a pipe dream. And, if there's a bright light in this pandemic, it's the work of the scientists who developed these vaccines in record time. On the dark side, Australia has endured major issues related to procurement and distribution, both of which are Federal Government responsibilities. We've been told by the Prime Minister: 'It's not a race, it's not a competition.' If this isn't the race of our lives, I don't know what is!

The Future

The sad fact is that zoonotic diseases will continue to rampage across the planet as long as we plunder our natural environment and the animals that live there. The list of existing zoonotic diseases is scary – Ebola, Zika, SARS and MERS (both coronaviruses), Swine flu, Ross River fever, Lyme disease and many, many others. Worse still, epidemiologists warn us that there are more to come if we continue our pattern of destruction and abuse of the world around us.

Deborah O’Brien - Writer

29 June, 2021

Bibliography and Further Reading

https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/masks-are-not-a-panacea-but-are-the-step-we-needed-to-take-20200720-p55dqh.html

https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/stories/pneumonic-influenza-1919

https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2020/jun/economic-effects-of-the-spanish-flu.html

http://www.gp.org.au/SpanishFlu.php

https://www.publish.csiro.au/ma/pdf/MA20048

https://tvblackbox.com.au/page/2020/05/28/lest-we-forget-this-week-on-australian-story/

Matt Bamford, ABC Radio, ‘Coronavirus response may draw from Spanish flu pandemic of 100 years ago’