Book Review: ‘Lake Hill’

by Margareta Osborn

When Margareta Osborn’s new novel, ‘Lake Hill’ arrived in the post, I was busy planning a family wedding and finishing a manuscript of my own. Reluctantly I put the book aside, awaiting a time when I could read it at my leisure. Last weekend, with the wedding successfully over and my own book safely in my agent’s hands, I gleefully hunkered down by the fire, ready to escape into Margareta’s latest rural romance.

The beguiling cover sets the mood, while the vivid descriptions of glistening lakes, lush pastures and big skies will transport you to Gippsland, a place so lovingly described in all of Margareta’s novels that it verges on being a character in its own right rather than a mere backdrop.

But there’s much more to ‘Lake Hill’ than the scenery – this is a novel that straddles genres, encompassing romantic elements but also some seriously dark issues as well as a good dose of mystery and suspense.

Two decades ago, teenagers, Julia Gunn and Rick Halloran, went their separate ways after a fleeting summer romance. Now in her thirties and recently widowed, Julia has decided to start a new life running a café at Lakes Entrance. On her way to the coast, a rockslide damages her car and she finds herself marooned in the mountain village of Lake Grace. After hitching a lift into town, she has no option but to stay at the local pub until the car is fixed. And guess who owns the pub? None other than Rick Halloran, who’s now a celebrity, thanks to his famous mother and his own success as a sculptor.

Reunion stories offer unique possibilities for creating dramatic tension. That’s because the two protagonists will bring a heap of emotional baggage to the reunion – their shared back story and the lives they’ve led independently in the time they’ve been apart. And if one or both has been carrying a torch for the other, well, that makes the reunion even more poignant and emotionally charged.

When Rick walks into the bar of the Lake Grace pub, Julia recognises him right away, and old memories come flooding back. For his part, Rick takes a considerable time to realise that the attractive woman with the fancy (albeit damaged) car is actually the shy bookish girl from his past. And when he does work it out, he’s not exactly happy to see her. In fact, he’s just plain surly.

What really happened all those years ago? Why did they go their separate ways? What has happened to each of them in the intervening time? And will the spark they felt as teenagers still be simmering twenty years later? The answers to those questions make for a meaty page-turner.

The dialogue is snappy, the characters nuanced, and the descriptive passages evocative. But what really grabbed me were the ‘knock-you-for-six’ twists. I can usually sense a plot twist coming chapters away, but not this time.

In a nutshell, ‘Lake Hill’ brings us a gripping and bittersweet story of second chances and lost opportunities. And if you’re the kind of reader who enjoys a blend of romance and mystery set against a bucolic backdrop, this novel could be the perfect addition to your reading list this winter.

Margareta’s website: http://margaretaosborn.com.au/

Buying details: https://penguin.com.au/authors/49-margareta-osborn

Deborah O’Brien

26 June, 2017

Film Review: ‘Their Finest’

In the mid-1980s, graphic novelist Alison Bechdel came up with a simple question to assess the level of sexism in a film. It is known appropriately as the Bechdel test. Here’s the question: Does this film feature at least two female characters who talk to each other about something other than a man?

In 'Their Finest’, directed by Lone Scherfig, a Welsh copywriter by the name of Catrin Cole (Gemma Arterton) ponders the same question, but it’s 1940 and women’s dialogue is referred to as ‘slop’. However, the Ministry of Information’s Film Division, headed by a pompously majestic Jeremy Irons, realises it’s necessary to engage a largely female wartime audience. As a result, Mrs Cole is enlisted to provide the ‘feminine perspective’.

Based on Lissa Evans' novel, ‘Their Finest Hour and a Half’, this film is a charming and ultimately moving story about British filmmaking during the Blitz. It’s a time of sweeping social change when women are keeping the home fires burning and some of them have no intention of being ‘put back into their box’ when the War is over.

This is also a film about making a film – under the constraints set by the Ministry of Information’s Film Division, which require that the storyline be ‘authentic and positive’ in order to boost public morale at a time when Britain’s fate seems increasingly bleak. The British Expeditionary Force has just been evacuated from Dunkirk, France has fallen, Britain is besieged by German air raids and America is pursuing a policy of neutrality.

There’s a stellar British cast led by a beguiling Gemma Arterton and a deglamourised Sam Claflin as the lead writer, together with the aforesaid Jeremy Irons in a cameo which gives him a chance to declaim the rousing St Crispin’s Day speech from 'Henry V'. Bill Nighy as Ambrose Hilliard steals the show in his role as a self-absorbed sixty-something former leading man who is now offered only minor roles. It’s a part which allows him to overact to his heart’s content and even break into song.

With the approval of the Ministry of Information, the writers, Tom Buckley and Mrs Cole, decide upon the true story of twin sisters who set out in their father’s boat in an attempt to cross the Channel and evacuate British soldiers from the beach at Dunkirk. But soon the writers find themselves required to include an American character for the US market and to alter their script in other ways to meet the demands of their masters. Until the very end, the movie is referred to as the ‘Dunkirk film’ but astute viewers will guess the eventual title from the start.

Being a big fan of British films of this era, I loved the references to actors and movies from the period but you don’t have to be familiar with them to enjoy the film.

There are fascinating insights into the writing process which will resonate with all you writers out there. When Mrs Cole delivers her rather lengthy script to Tom Buckley, he tells her to cut half of it. ‘Which half?’ she asks. The one you don’t need, he replies. A script, she is told, is ‘real life without the boring bits’.

In a nutshell, ‘Their Finest’ is a charming and bittersweet tribute to British filmmaking during the darkest days of World War II and the pivotal role of women on the home front.

Deborah O’Brien

16 April 2017

Film Review: Alone in Berlin

Set in Nazi Germany from 1940-1943, 'Alone in Berlin' presents a series of simple acts of resistance by a dour middle-aged couple whose soldier son has died in the Battle of France. This is a strong story made even more powerful by the fact that it is inspired by real people and events, as portrayed in Hans Fallada’s 1947 novel, ‘Jeder stirbt sich allein’ (‘Everyone Dies Alone’).

It's June 1940, and Berliners are celebrating the German victory over France and the signing of an armistice in the same French railway carriage where Germany surrendered in November, 1918. We first meet Otto and Anna Quangel in their Berlin apartment as they are delivered a letter from the Wehrmacht informing them their only son has been killed on the battlefield. Otto is a Nazi Party member and Anna is involved in the NS-Frauenschaft - the National Socialist Women's League, but both begin to question their alliance to the Nazi regime.

Overcome by quiet grief, Otto begins to write postcards urging others to resist the Nazis and decrying their manipulation of the truth. With Anna’s help, Otto leaves these subversive cards at random locations across the city - under doors, in stairwells. The messages are headed ‘Free Press’. There is, of course, no free press in Nazi Germany. When Hitler came to power in 1933, he forcibly eliminated all his opponents, settling old scores with left-wing newspapers like the 'Munich Post', whose premises were wrecked by the ‘Brownshirts’ and its courageous journalists imprisoned and subsequently murdered. Having just written about the demise of the free press in Nazi Germany in my new novel-in-progress, I found the events of the film particularly affecting.

There are finely nuanced performances from the leads, Brendan Gleeson as Otto and Emma Thompson as Anna, together with Daniel Brühl, who gives an outstanding performance as the police inspector trying to track down the anonymous author of the postcards and being pressured by the Gestapo to solve the case. The acting is so understated that when the violent moments come, they are even more shocking.

The streets of Berlin in the early 1940s are depicted in muted monochromes by director Vincent Perez and his cinematographer, Christophe Beaucame. One exterior scene shows us the Gestapo headquarters covered in snow, the only touches of colour being the red background of the swastika banners hanging from the building.

From the film’s credits I discovered that the actual filming took place in Berlin itself and also in Cologne and a town called Görlitz in Saxony, which, Wikipedia tells me, served as a backdrop in 'The Grand Budapest Hotel', 'The Reader' and 'The Book Thief'.

What I particularly like about this film is that they’ve taken the time to get the details right – the dialogue, the historical facts, the costumes, even the posters promoting the Hitler Youth.

At a time when the concept of truth as an absolute value is being threatened by ‘alternative facts’, this film should resonate with all of us. The Quangels' brave acts of 'civil disobedience' may not have had the effect they anticipated in that most of their postcards were promptly handed over to the Gestapo; even so, their little campaign of resistance demonstrates that ordinary people can find ways to express their opposition, even in a tightly controlled society.

In many ways, ‘Alone in Berlin’ is a dour film, much like the couple at its centre, but it's also one of the most moving and powerful films I’ve seen in a long time.

Deborah O’Brien

4 March 2017

My Top Six Tips

for Aspiring Writers of Historical Fiction

Image: DOB

I’ve written all my life but it wasn’t until 2009 that I made a serious attempt at a full-length work of historical fiction, and even then the story alternated between the past and the present – 1975 and 2009/10. I just didn’t have the courage or the skills to set it entirely in the past. For more than a year the manuscript went back and forth between my desk and various assessors. In the process, I learnt to embrace revisions rather than fear them and eventually it became a different (and better) novel than the one I’d started.

Just when I’d completed a polished first draft, incorporating all the feedback the experts had given me, real events overtook my story. In the winter of 2010, Kevin Rudd was deposed, Julia Gillard became PM, and my novel about Australia’s first female Prime Minister was kaput. There were many sleepless nights as I experimented with other political and ambassadorial roles for my female protagonist (first President of a hypothetical Australian republic, Foreign Minister, High Commissioner to the UK) but it just wasn’t the same.

So, I consigned that unfortunate manuscript to a digital drawer (where it remains to this day) and started another book, which went on to become 'Mr Chen’s Emporium'. I was still uncomfortable about setting an entire novel in the past so I shifted back and forth between the 1870s and the modern day. When the book came out, I was nervous about what people would think of my foray into historical fiction. But, much to my surprise, the critics and the readers liked the 1870s storyline (some weren’t so happy with the contemporary thread) and the book became a bestseller.

After 'Mr Chen’s Emporium', I began to feel more comfortable about writing historical fiction. What I liked best about it - and still do - is the element of time travel, the sense of escapism, the notion of journeying into the past and becoming immersed in another world. The novelist L.P. Hartley, author of 'The Go-Between', famously said:

‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.’

I enjoy exploring those ‘foreign countries’, whether it’s the 1870s in 'Mr Chen’s Emporium', the 1880s in 'The Jade Widow', 1966 in 'The Rarest Thing', or the 1930s and 40s, which is the backdrop for my next novel, 'Camille Dupré'. This will be my first historical story set outside of Australia. After four historical manuscripts, I feel ready to make the trip. France was the obvious choice because I know it well and speak the language. Could I have set a novel in Russia or China, for example? I don’t think so. Not without living there and knowing the language.

So, what are my top six tips for writing historical fiction?

1. Do your research. Familiarise yourself with the period. Live there in your imagination until you know it intimately, and then just start writing. You can fact-check the tiny details as you go along – that’s the advantage of having the internet.

2. If there are films and musical recordings from the period you have chosen, immerse yourself in them. Listen to the way people spoke and the words and phrases they used.

3. Search the National Library of Australia’s amazing resource, Trove, for digitised newspaper and magazine articles. There’s nothing better than reading the news as it happened. And if your story is set in Australia between 1933 and 1982, may I suggest Trove’s digitised copies of the 'Australian Women’s Weekly' (trove.nla.gov.au/aww) which will give you a window into the morés and preoccupations of ordinary Australians over the decades.

4. After you’ve done all the research, digest it thoroughly but resist the temptation to dump chunks of historical information into the story, no matter how fascinating you might find them. Too much historical detail can overwhelm a manuscript and slow down the narrative. It’s a balancing act. The historical infrastructure of a novel should act like the electricals in a house – everything should work properly, but you really don’t need to see the wiring.

5. Don’t try to retrofit modern beliefs and perspectives onto the past. 'Mr Chen’s Emporium', for example, deals with the way white colonial society discriminated openly against Chinese miners.

Racial discrimination is something I deplore but that was the norm in the 19th century and it needed to be depicted accurately. Although several characters in the book speak out against prejudice. I had to make it clear that theirs was not the prevailing view.

6. Make your dialogue sound right for the period. Avoid obvious anachronisms of the kind that will jolt a reader out of the world you’ve created and right back into the 21st century.

And most importantly, enjoy the time travel.

Deborah O’Brien

18 February

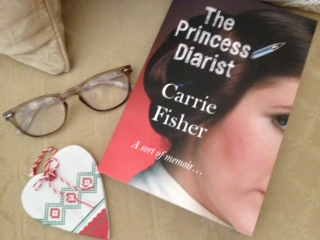

![]() Book Review:

Book Review:

'The Princess Diarist', Carrie Fisher

PREFACE: Carrie Fisher tragically died of a heart attack on December 27 2016, six days after I wrote this review. Dazzlingly talented, Carrie has left us a legacy of wonderful written work, as well as her performances in film and television. She had only just started writing advice columns for 'The Guardian', full of gentle, caring and constructive advice for young people facing bipolar disorder and other problems. And, of course, there's her funny and poignant 'sort of memoir', 'The Princess Diarist'. Here's my review:

Every year I indulge myself by buying a book to read on Boxing Day. Usually it’s an autobiography of the celebrity kind. In the past I’ve discovered some treasures including Dawn French’s 'Dear Fatty', William Shatner’s 'Up Till Now' and Mia Farrow’s 'What Falls Away'. I’ve also bought myself some duds (no names, no pack drill). A few weeks ago I happened upon an extract from Carrie Fisher’s 'The Princess Diarist' which was featured in 'The Guardian' (below). I started reading it, assuming it would be a typical celebrity tell-all about her recently revealed affair with Harrison Ford (which took place during the filming of 'Star Wars' in 1976). Instead I was riveted by the best writing I’ve encountered in a long time - funny, masterful and achingly poignant.

Intrigued by the extract, I went off to the bookstore to get hold of the paperback, intending it to be my 2016 ‘Boxing Day book’. I’ll just have a quick browse, I told myself when I got home. But I couldn’t put the book down. And yes, I finished it in a single sitting.

In 1976 Carrie Fisher was nineteen, the daughter of a glamorous movie star, Debbie Reynolds, and the product of a broken home (her father, singer Eddie Fisher ran off with Elizabeth Taylor when Carrie was a toddler). So it’s not surprising that she had self-esteem issues and was looking for love. Harrison Ford was in his thirties and married.

When Fisher embarked on a relationship with the wryly taciturn Ford, she was under no illusion that when the filming ended, so would the affair. For his part, Ford didn’t promise her anything in return, just the pleasure of his company.

Although Fisher never raises the possibility in the book, I suspect Mr Ford might have fallen just a little in love with her during their affair. How could he not? Fisher was (and is) as witty as all get-out and the crew adored her. When sixty-year-old Carrie Fisher looks back at photos of herself from 1976, she can see that she was as ‘cute as a button’. At the time, however, her self-image was askew and she considered herself plain and chubby.

The first part of 'The Princess Diarist' is a narrative, while the latter portion includes diary extracts and poems, discovered when Fisher was going through a box of written work she'd forgotten about. It’s worth noting there are no sex scenes in the book - Fisher has made the wise choice to keep the private stuff just that.

You don’t need to be a 'Star Wars' fan to enjoy this memoir (or 'a sort of memoir' as she calls it on the cover). Anyone, who’s been nineteen and obsessively in love with someone who’s obliging but spoken for, will ache for Carrie Fisher. Reading her poems and diary entries from that period is like peering into her nineteen-year-old soul. In many ways, she was very brave in making her 'primary sources' public.

On a technical level, Fisher is a consummate wordsmith. The text bursts off the page with its originality, humour and pathos. There are puns galore, but this is not an exercise in showing off; every element of word-play, every metaphor earns its place in the book.

If you’re waiting for a response to 'The Princess Diaries' from Harrison Ford, don’t hold your breath. Fisher’s sympathetic and engaging portrait of a very private man is perhaps as close as we’ll get to knowing the ‘real’ Ford. As for Ms Fisher, she’s been carrying a torch for Han Solo for the past forty years.

And who could blame her?

You can read an extract courtesy of 'The Guardian'.

Deborah O’Brien

21 December 2016

Subcategories

Home in the Highlands

Home in the Highlands blogs