OR

You Can't Judge a Book by its Word Count

When a friend’s little boy found out I was a writer, the first thing he asked me was: ‘How big is your book?’ Nobody had ever posed that question before and I was quite taken aback. What exactly did he mean? Did he want to know the dimensions, or was he referring to the number of pages?

Impatient with my hesitation, the little boy persisted, ‘How thick is it?’

So I indicated the width of the spine with my fingers. (MR CHEN'S EMPORIUM and THE JADE WIDOW are the same length - about 350 pages. I'm not sure how it happened; it certainly wasn't planned.)

‘Wow!’ the boy replied.

No doubt that seemed like a very big book to a seven-year-old, but in point of fact, both novels are around the average length for adult commercial fiction. Nevertheless, the boy's reaction reminded me that a weighty tome possesses a certain gravitas, whether it deserves it or not.

Publishers tend to have a preferred word count for novels. It's a range rather than a specific number and it will differ from publisher to publisher and according to genre. The minimum length might be around 70,000 words, and it could range up to 200,000 and possibly more. Look at WAR AND PEACE - if I recall correctly, it's over half a million words! Tolstoy aside, a novel can, of course, be too long. I won't mention any specific examples, but I'm sure you've encountered a few that could have done with a heavy pruning.

As a reader, it’s been my experience that some of the finest novels are contained within the slimmest of volumes. George Orwell’s ANIMAL FARM, for instance, is only 41,100 words (wiki.answers). My well-thumbed copy of THE GREAT GATSBY – with Robert Redford and Mia Farrow on the cover – is 188 pages. Ian McEwan’s beautifully crafted novel, ON CHESIL BEACH is 166 pages (2008 Vintage edition) with generous spacing between the lines. I suspect it's about 45,000 words. Likewise, Ray Bradbury’s ground-breaking FAHRENHEIT 451 (discussed elsewhere on this site).

There can be something intrinsically elegant – not to mention covetable – about a slim volume. Take Alan Bennett’s charmingly seditious novella, THE UNCOMMON READER. The publishers have played up its brevity by producing a small hardcover book (a mere 18 x 13 x 1.25cm – yes, I measured it!) with an embossed dust jacket and patterned endpapers. When I saw it in the bookshop, I just had to have it!

Recently I’ve written a manuscript, which is not quite 50,000 words in length. The story revolves around a quirky cast of characters, brought together by a common interest. So far, only my family and a few trusted friends have seen it. I really like this book, but the problem is that it's just too short. Could I pad it out with additional subplots or incorporate extra scenes? I don’t think so. I’ve said what I have to say, and to my mind, it’s finished. So where do I go from here? Well, I’ll probably put it in the bottom drawer for a while. I hear novellas are coming back into fashion, so you never know . . .

Do you have any ‘thin’ novels that you really love? Please let me know.

Deborah O’Brien

September 2013

![]() Fairytale Turrets and Other Fantasies

Fairytale Turrets and Other Fantasies

Ever since I was a small child, I’ve dreamed of living in a fairytale castle, complete with turrets. I blame it on Walt Disney’s ‘Sleeping Beauty. I adored that film – the music, the princess and especially the magical castle with its soaring towers, castellated parapets and sweeping staircases.

‘When I grow up,’ I told my mother, ‘I want a house just like that.’

Did I get my fairytale castle? Of course not. Instead, I made it my mission to visit as many castles as I could. My personal favourites are:

- King Ludwig’s Neuschwanstein near Füssen in Bavaria. An exercise in wish-fulfillment and fantasy in the most breathtaking location

- the elegant Château de Chenonceau, spanning the River Cher and celebrating its 500th birthday this year

- Bodiam Castle in East Sussex, a 14th century medieval fortress with its own moat. And Sissinghurst in nearby Kent for its Elizabethan tower and gorgeous gardens.

As a novelist, I’ve managed to incorporate some of my unfulfilled architectural dreams into my stories. In MR CHEN’S EMPORIUM, it’s the Old Manse, a Victorian gingerbread house with fancy bargeboards and arched attic windows.

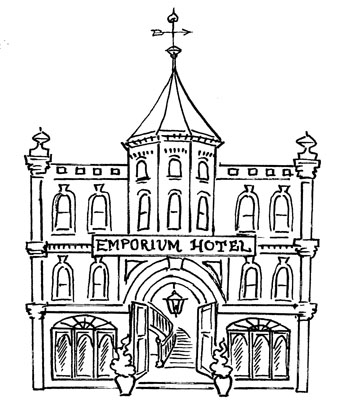

In my new book, THE JADE WIDOW, which is set during the mid-1880s in the fictional Australian town of Millbrooke, the centrepiece is an establishment called the Emporium Hotel with its own two-storey turret, housing the luxurious Oriental Suite.

You can see the entrance on the cover of the book – an arched portico guarded by a pair of Chinese urns containing jade plants, or money trees, as they’re often called. Inside the foyer we catch a glimpse of the Jade Widow herself, the hotel’s proprietor. She looks a little aloof. Perhaps the world has made her so.

a pair of Chinese urns containing jade plants, or money trees, as they’re often called. Inside the foyer we catch a glimpse of the Jade Widow herself, the hotel’s proprietor. She looks a little aloof. Perhaps the world has made her so.

The Emporium Hotel boasts all the latest innovations of the era: internal bathrooms, a domed leadlight ceiling in the conservatory, and one of Australia’s first ‘ascending cabinets’. The only limitation on its design is the historical context. It would be anachronistic, for example, to have electric lighting or an electric lift.

It’s the kind of place where you would expect dreams to come true. A little corner of happy-ever-after land. But real life isn’t a fairytale, and happy endings aren’t easy to come by – whether you live in a turreted castle or the most humble little cottage.

Deborah O'Brien

August 2013

Winters can be rather bleak in my part of rural New South Wales. This year, however, the average July daytime temperature was a mild 13 degrees as opposed to a historical mean of 11 degrees.

Already the roses are starting to bud, new lambs are gambolling in the paddocks and I haven’t seen a morning frost in days. Am I jinxing myself by telling you this? Probably. After all, there’s still another month remaining until winter is officially over. And here in the Southern Tablelands, winters are wont to last considerably longer.

Around my garden the wattle trees are in bloom – a glorious, glowing yellow. They’re such a contrast to the bare tracery of branches on the deciduous trees.

This morning my dog and I went out early for some platypus spotting down by the creek. Instead, we found a flurry of ducks, some beautiful cows and a small flock of sheep with three adorable lambs.

Deborah O’Brien

August 4, 2013

In February of 1885, the news of General Gordon’s death during the fall of Khartoum reverberated around the British Empire, even to the far-flung Antipodes. Ever since the previous year, Australians had been anxiously following the story of the besieged general and his garrison, courtesy of newspapers such as The Sydney Morning Herald and the Argus.

During the previous decade the reporting of news had been revolutionised by a system of electric telegraph lines and submarine cables, commonly known as ‘the Extension’, joining Australia to London via Singapore and Bombay. In 1884 the telegraph line connecting Khartoum to Cairo was severed by rebels, and so were communications. After that, the only means of contacting the outside world was by letter, usually sent by steamer sailing up the Nile. Sometimes the mail was hijacked. And even if a letter did get through, it would take weeks to reach London.

Consequently rumours swirled as to Gordon’s fate. Although he was killed on January 26, news didn’t reach London until the second week in February. Australian newspapers reported his death on February 12. By the 14th the NSW government had already offered to send a contingent to participate in a campaign to avenge his death.

Who was General Gordon, anyway? Well, at the time, he was considered one of the British Empire’s greatest heroes. He had served in China where he was dubbed ‘Chinese Gordon’ by the emperor. In Africa he’d fought the slave trade. In the wake of a rebel uprising in the Sudan, there was pressure from the British public and the Opposition to send Gordon to sort out the situation and evacuate the Egyptian forces stranded there. The Prime Minister, William Gladstone reluctantly agreed. But soon the General, who’d been sent to save the day, found himself besieged and in need of being rescued.

Although very few modern-day Australians realise it, Gordon’s death precipitated the self-governing colony’s first involvement in a foreign war. It was a brief campaign involving about eight hundred men raised in New South Wales largely from volunteers, but also from the First NSW Regiment.

Most people embraced the war, seeing it as ‘a great adventure,’ but there were some who disagreed with the NSW involvement – The Bulletin newspaper, the former Premier, Sir Henry Parkes (who had retired from politics but stood again to protest the war) and protesters among the general populace. In THE JADE WIDOW I describe the rush to enlist, as well as the embarkation day only a couple of weeks later, when a public holiday was declared and tens of thousands of Sydneysiders lined the streets to watch the Contingent march from Paddington Barracks to the Quay.

There were no deaths in action, largely because there was very little action at all. By the time the NSW Contingent arrived at the end of March, it was almost over. They were part of an assault on the desert settlement of Tamai; then things fizzled out. After that, the Australians were sent to help protect the building of the Berber railway. In early May they received news they would be going home. There were nine deaths in total, as a result of disease. Two privates made it home, only to die in the Manly Quarantine Station overlooking Sydney Harbour.

Afterwards, there were parades and banquets, medals and souvenir booklets. The campaign was a precursor of bigger, deadlier Imperial wars to come – the Boer War in South Africa and then the Great War, in which over 400,000 men enlisted from a population of around five million.

Echoes of that war haunted my childhood. In the aftermath of Gallipoli, my grandfather, along with a bunch of other patriotic young men from central-western NSW, who called themselves the ‘Boomerangs’, marched to Bathurst to enlist. (See the Australian War Memorial website for more about the trip.) For my granddad, Ted, it was a very personal decision.

His older brother, Arthur, had been killed at Gallipoli on 7 June, 1915. Only twenty-two years old, Arthur was a six-foot-tall shearer and a real larrikin, if his military records are anything to go by. I wish I could have met him.

Ted joined General Monash’s Third Division. In June, 1916, he was gassed near the Belgian village of Messines. He survived the mustard gas but was permanently incapacitated as a result.

In a way, THE JADE WIDOW is a tribute to my grandfather and my great-uncle and the sacrifices they made. Two valiant young men, who should never have been there in the first place. The conflict of 1885 was the foreshadowing of horrific wars to come. Visionary men like Sir Henry Parkes saw the future and opposed the colony’s involvement in the Sudan. He feared it would set a tragic and dangerous precedent. But voices like his were drowned out in all the righteous flag-waving and jingoism.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose …

Read more about the Sudan campaign at the Australian War Memorial website.

Steamship pic courtesy of Jan N's heirloom family scrapbook c. 1890

Deborah O’Brien

August 2013

FILMS & TV (23)

Film Review: 'Alone in Berlin'

Film Review: 'The Fault in Our Stars'

Film Review: 'The Grand Budapest Hotel'

Film Review: 'The Hundred-Foot Journey'

Film Review: 'Magic in the Moonlight'

Film Review: 'The Monuments Men'

Film Review: 'Saving Mr. Banks'

Film Review: 'Twelve Years a Slave'

Film Review: 'The Water Diviner'

My Four Favourite Stories about Platonic Love

My Top Five Films about Politics

A World Without Books: Fahrenheit 451

A World Without Downton: the 'Downton Abbey' Finale

HOME IN THE HIGHLANDS (5)

Home in the Highlands: I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas Dec 2021

Home in the Highlands: Autumn May 2018

Home in the Highlands: The Flying Carpet July2018

Home in the Highlands: A Tale of Two Chandeliers April 2018

Home in the Highlands: The Secret Garden April 2018

Home in the Highlands: Finding the Dream Home March 2018

COUNTRY LIFE (7)

The Case of the Missing Monotremes

When a Platypus's Fancy Turns to Love

ON WRITING (30)

An Aspiring Author's Guide to Book Jargon

Book Review: 'Kakadu Sunset' by Annie Seaton

Book Review: 'Lake Hill' by Margareta Osborn

Book Review: 'The Princess Diarist' by Carrie Fisher

Crafting Characters (Guest Post for 'Hey Said Renee')

Five Things I Love About Writing Fiction

My Four Favourite Stories about Platonic Love

My Five Favourite Books about Unrequited Love

The Five Books That Have Influenced Me Most

My Top Three Tips for Aspiring Authors

My Top Six Tips for Writing Historical Fiction

Never Write When You're Hungry

Q&A with Annie Seaton, author of 'Kakadu Sunset'

Rose Scott Women Writers' Festival 2014

A World Without Books: Fahrenheit 451

DOGS (7)

RECIPES (2)

SEASONS (7)

HISTORY and NOSTALGIA (8)

Déja vu: Lessons from the Spanish Flu

A Gallipoli Story: Finding Uncle Arthur

A Gallipoli Story: The Lost Shearer

Recreational Sewing in Cesarine

The Victorian Art of Scrapbooking

CAMILLE DUPRE

MR CHEN'S EMPORIUM (8)

Inspirations for 'Mr Chen's Emporium'

The Jade Widow@Mr Chen's Emporium

THE JADE WIDOW (7)

Fairytale Turrets and Other Fantasies

The Victorian Art of Scrapbooking

A PLACE OF HER OWN (4)

Launching 'A Place of Her Own'

My Next Book: 'A Place of Her Own'

THE TRIVIA MAN (11)

Meet the Cast of 'The Trivia Man'

The Nerd as Hero (Guest Blog at Dark Matter Zine website)

'The Trivia Man' Trivia Competition

THE RAREST THING (4)

'The Rarest Thing' Blog Tour 2016

Subcategories

Home in the Highlands

Home in the Highlands blogs